This piece has been co-authored by Chloe Treger, Ian Bird, Indy Johar , Jayne Engle, Mallory Willson, Laurence Miall, Patrick Dubé, Robert Plitt, Sophie Mechin and Sara Lyons. It was originally posted on Medium.

On the occasion of the inaugural Future Cities Summit, we are sharing this provocation. At the Summit we have heard multifaceted perspectives on the great transition that our cities are facing, from addressing the challenges of the future of work, inequality, planning, affordability, climate change, resilience and next generation governance to name but a few. Many of these challenges are underpinned by a need to invest in our civics, commons and public goods — be it preventative health or our environmental biosphere.

The purpose of this provocation is not to provide answers (yet!), but rather to stimulate and acknowledge the need for a new conversation, share some real-world examples and share the pathway for a new collaborative lab.

1) Risk like never before

Increasingly, actors globally — whether international organisations,institutional investors, civic groups and private foundations — are recognising that we do not have the financial instruments, models or practices, nor the specific strategies, to cope with the interconnected challenges of comprehensive environmental degradation and growing social inequity.

Increasingly probable long-term threats include 800 million people at risk from sea-level rises and 800 million jobs at risk from automation. Everyday risks are growing as well, such as fatal heat-waves, unmitigated flood risks, and societal epidemics like loneliness remind us daily of the collective failure to create equitable, resilient cities.

Canada is in many ways a leader of urban innovation. Home to 3 of the top 10 liveable cities, with a first-class knowledge base, it is not exempt from these present, and future, pressing risks. First, at present, the Canadian system is failing to provide even the most basic of human rights on Reserves, and creating barriers for Indigenous people to flourish and grow thriving local economies. Secondly, our cities are failing to find inclusive ways to cope with population growth, becoming increasingly unaffordable, driving inequalityacross our nation. Tackling these dynamics with a governance, fiscal and financial system that structurally underfunds our municipalities (even though they are responsible 60 per cent of infrastructure) and entrenches inequality, is an immense and daunting challenge.

2) A time for civic capital & civic asset management

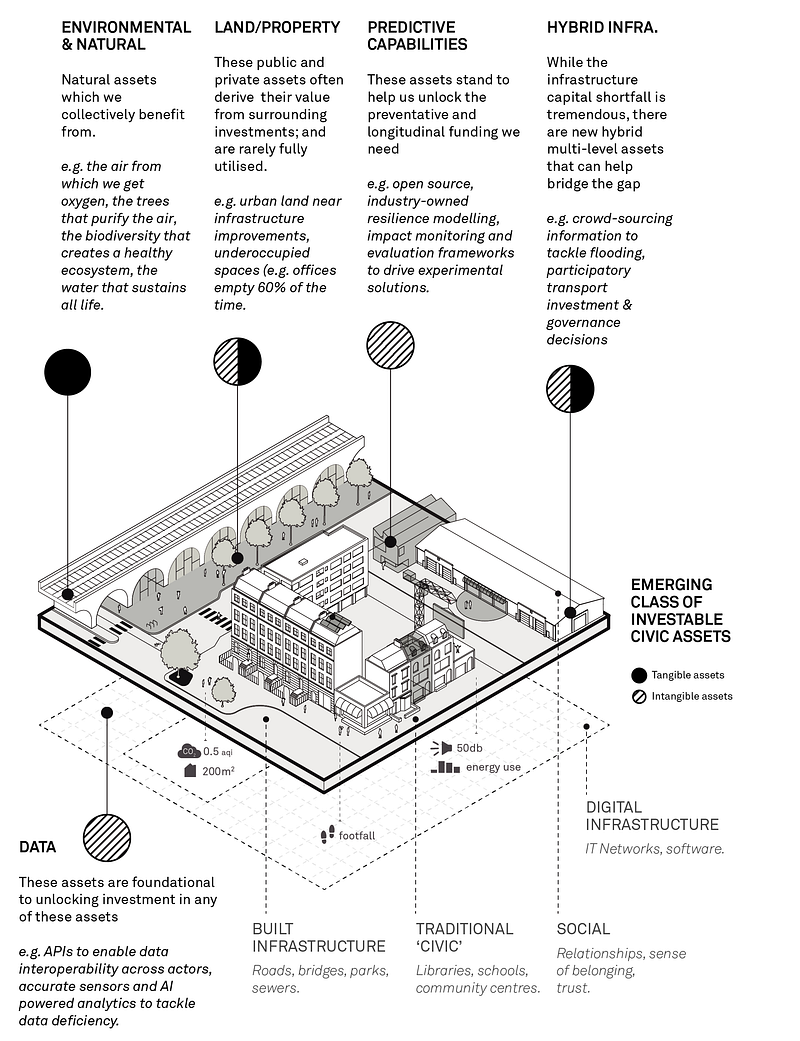

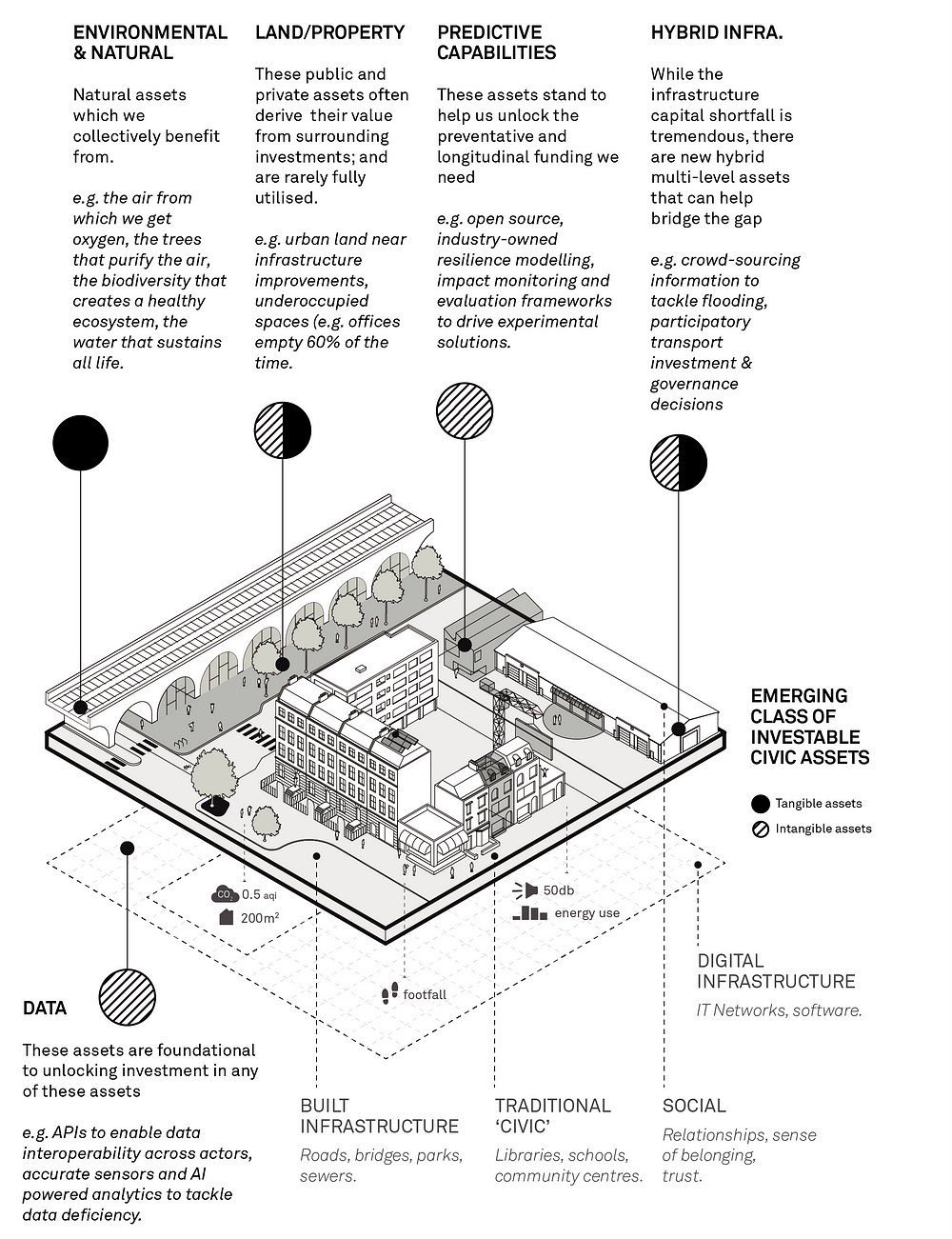

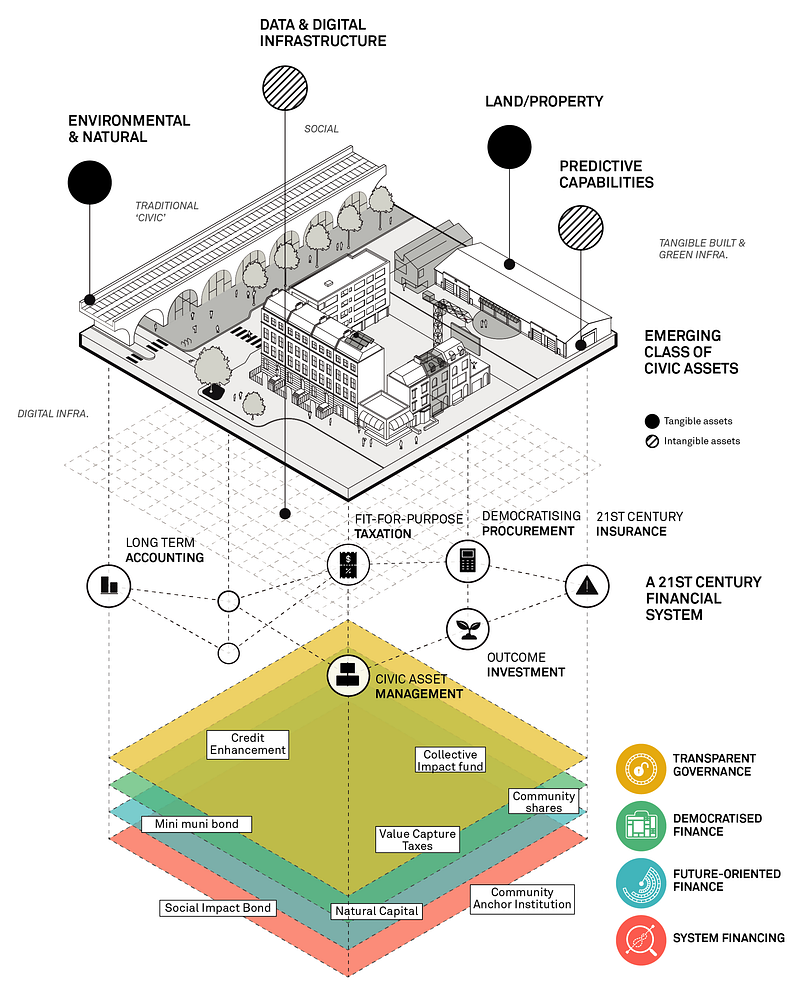

We believe that one of the best ways to tackle these challenges is to invest in 21st century civic assets and grow our civic capital. Just as financial capital includes a range of asset classes (such as equities, debt, and cash) that are invested with an expectation of financial returns, civic capital includes a range of asset classes which we can collectively invest in with an expectation of generating civic returns — that is, returns that benefit our cities collectively.

Civic assets go beyond municipal ‘assets’ (those that show on a city’s balance sheet, e.g. streets, sewers and water systems). They include tangible assets, such as built infrastructure and natural assets, like the aquifer whose health reduces the cost of our flood-mitigation strategies and provides potable water. They include intangible assets as well, with a recent example of flood recovery in Jakarta showing how these assets (including data and social capital) created an innovative response based on latent civic duty and crowd-sourced tweets to deal with the disaster.

While we all understand and are equipped to invest in mitigating personal future risks, including the asset-manager who diversifies their client’s portfolio accordingly or the parent who puts aside for their children’s education — we argue that we are failing, as a society, to invest in our essential shared assets our civic assets. Part of the reason for this is the (to date) impossibility of quantifying, and analyzing these diffuse risks and value creation but this is no longer the case.

3) An age of technological advances

In an age of multiple technological revolutions we can:

- Monitor that private home-owners stand to benefit from 167 per cent increase in land-value — through transparent real-time immutable land registries

- Analyze increasingly accurately the $68B that the Canadian health service stands to lose by not preventing chronic illnesses — through big data and AI analytics

- Optimise rescue operations, steering resources based on crowd-sourced tweets and participatory governance mechanisms

- Grow collective ownership and individual value creation by separating assets into their parts thanks to the reduction in administrative costs due to almost-zero computational processing cost

Alone, this new information will not foster a new relationship between the private and civic. We need to create the investment case, through innovative governance, financing and measurement approaches — that moves us towards an asset-based approach which is focused on converting this new knowledge (gained through new data and information) into the wisdom to act for our collective future benefit.

This is not the first time the world has needed innovation in how capital flows to support civic assets. In the 15th century, Henry VIII created a ‘betterment’ levy to capture value from flood defences; post-great fire London invented private property insurance to fund fire engines in the 17th century ; and industrialists created mutually owned credit-clubs in the 19th century to unlock mass house building.

In each age, civic-minded individuals or institutions deployed newly available tools of regulation, investment, accounting, taxation or procurement to answer the pressing shared challenges of their time, or invented new tools where necessary.

In the 21st century, with the rise of technologies mentioned above, we are seeing widespread innovation from a range of actors from different sectors — public, private, and civil society: from new public-private payment-for-successfinancing schemes which help to leverage private capital as well as drive evidence in policy-making, innovative insurance products that help to drive long-term investment decisions by monetising the avoidance of catastrophic risk, to alternative currencies which operate as mutual credit systems which unlocks financing for small businesses by democratising who gets to issue capital.

Innovation is helping us build pockets of civic capital. In order to do this at scale we urgently need to challenge the often hidden ‘dark matter’ which influences the way we raise and steer capital, creating a multi-value long-term accounting system that highlights interdependencies; using cross-silo socially beneficial procurement strategies which leverage what is already being spent; legislating for the real-time taxes which can represent an increasingly accurate picture of public-private value flows; developing innovative insurance products that manage to mitigate collective risk as well as growing our common narrative around best-in-class system investment and asset management portfolios to make our system for raising and steering capital more systematic, long-term, democratic and transparent.

4) Civic Futures

While the task set out above — to create a more civic future — is large, we are not starting from square one. There already exists a world of civically minded individuals and organisations ideating, prototyping and iterating this future (we will be publishing more on this in the new year).

However, scaling these seeds of change up to create meaningful change is far beyond the ability of individual organisations acting in isolation. We must therefore build a sense of shared civic understanding — recognising in our Canada context (as elsewhere) Indigenous land ownership, financial restitution, and self-determination are key elements of this new future — and growing our collective intelligence, capacity for experiments and drivers for change.

Getting to this shared civic attitude, and creating the mechanisms to convert this attitude to financial decisions, requires a new way of working, with new principles for organising that respect the complex and rapidly changing world we live in. Principles are being tested with different groups such as Capital Institute.

Rather than announce a strategy of our own, with an associated timeline that sets unlikely milestones that end up tyrannising (rather than propelling) the process, we are following an open and adaptive method which sets out principles for working, rather than a phased process, such as 90-day reflective sprints to break down the scale of the challenge to small actionable tasks. At the end of each of these sprints, which we commit to and work on transparently, we will reflect critically and iterate for the next sprint.

These sprints will involve actions with various aims, we believe these will includes:

- Open Researching & Visualising: to build the case for growing our civic capital. This involves investigating a range of topics — from analyzing the deficiencies in the status quo such as the human and financial cost of implementing non-individualised social care to new futures such as how we can use insurance to monetise the avoidance of civic risk. The data-visualisation, and designed provocations, will be key in order to engage those outside our echo chamber

- Hosting a public discussion: to build legitimacy around our civic capital mission. This will require creating the platform to host the discourse around the civic capital deficit, crowd-sourcing hypothesis around why that is and how to change it. It will invite a breadth of protagonists, from institutional investors who understand the relevance of asset-allocation portfolio tactics to citizens with lived experience of some of these societal risks in order to co-create an agenda for change. We do not think it will be sufficient to follow our old institutional closed think tank models of delivering research. The opportunity for do things differently has roots in new technology but also the urgent need to address the emerging concentration of wealth and power in Canada and the need to redress racism, patriarchy and colonialism.

- Advocating for change: to overcome the system lock-ins and barriers that might stand in our way of this civic future. Meaningful change is mostly hard to deliver, due to the often invisible influences of our institutional and organisational design (things like how we develop fiscal policies, what assets count as having a value on our municipal balance-sheets, how our KPIs and employee contracts re-focuses the prioritisation of our labour). On top of the public discussion to raise our appreciation for this, we believe certain stakeholders who have the capacity to bring about change need to be engaged. To do this, we are planning to engage these stakeholders through formal and informal channels and publish communications which bring coherence to our future vision. New definitions of progress and justice are required which integrate social justice and natural systems justice.

- Convening unlikely allies and applying a justice and equity lens: to create the spaces for co-creation between people who never sit in the same room. To do this, we will host events and design change labs that invite people from all walks of life. Part of what is needed is to shift power around who controls capital and how decisions get made. Leadership and action is needed to establish the responsiveness and accountability to people who have been systematically excluded through past and present intersection of patriarchy, racism and colonialism.

- Prototyping: to build the innovative mechanisms for growing our civic capital. Working with global and national partners, using the research and discussions, key potential financial mechanisms, procurement models, accounting frameworks etc. These will be co-created through a series of open hack-days and live experimentation through living lab-type contexts in the cities.

- Building the process for institutional capacity development: to build the experiments and proof cases for implementing this strategy. To do this we are in the process of designing ‘A Civic Capital Lab’, with which we plan to work with multi-stakeholder groups from specific cities around a specific mission to bring together our diverse energies around a shared mission. What this looks like in practice is yet to be determined: will it be about setting up specific platform organisations to host local impact movements; open workshops to map the issues and civic assets in a city; 100-day targeted campaigns on actionable deliverables (e.g. reduce asthma costs by 5 per cent) and/or multi-year modalities of system asset mapping, ethnography?

- Seeding the next generation of civic capital funds. All of the above is in service of growing our capacity to invest collectively in our civic capital; in order to truly grow this we need the large-scale financial capacity that can tackle the unprecedented challenges we are facing.

This provocation marks the beginning of exploring how we create a 21st Century Civic Future. We welcome you to get in touch, contribute and be part of this tomorrow — admin@civiccapital.cc

We would like to thank everyone at the Wasan Island convening — Stephen Huddart, Geoff Cape, Otis Rolley, Stephen Popovich, Terry Cooke, Derek Gent, Jon Shell, Mike Himbeault, Kathleen Llewellyn-Thomas, Mary Rowe, Eunji Kang, @AlexRyan, Sasha Sud, Paul Messer, Chloe Treger, Ian Bird, Indy Johar , Jayne Engle, Mallory Willson, Patrick Dubé, Robert Plitt, Sophie Mechin and Sara Lyons — and also all those that attended the ‘Financing the Great Transition’ Session yesterday at the Future Cities Summit.

This piece has been co-authored by Chloe Treger, Ian Bird, Indy Johar , Jayne Engle, Mallory Willson, Laurence Miall, Patrick Dubé, Robert Plitt, Sophie Mechin and Sara Lyons.

Civic Capital Lab is being formed as part of the Future Cities Canada initiative under the collaborative leadership & direction of Community Foundations of Canada, Maison de l’Innovation Sociale, MaRs, McConnell Foundation and Dark Matter Laboratories.